Art by Angelica Blevins

Sacred Servers

In the spring of a while ago, during a trip to Ireland, I had the chance to visit a sacred well. Sacred wells are pilgrimage sites — have been since pre-Christian Ireland — with pagan rituals adapting to and persisting through new Christian traditions over the last 1500 years.

The well was sheltered in a squat, stone hut. Its entrance was easy to spot by the amount of stuff — bright, eclectic piles of stuff — crowded around it and brimming from within. The walls and floor overflowed with meaningful objects, a mix of religious symbols and personal items rich with meaning. Votive candles, portraits of loved ones, saint’s medals, a statue of a house, a prayer card, a pair of crutches — all left behind by past pilgrims to focus and amplify their prayers.

The traditions of the well weren’t my traditions, but I felt a reverence for the place immediately. I unconsciously took off my hat at the entrance, walked softly down the passage way, dared not disturb the candles, photos, toys, and the tightly folded papers holding letters not meant for any human to read.

The friends I was with grew quiet as well; or rather, it was as if a type of profound quiet filled the place and we all followed its lead.

What was the source of that quiet — the source of the power and energy I felt there? Did it emanate from the well itself, an ageless power felt by those who discovered it? Or was it a collaboration with the land, an energy that accumulated with each person who left something of themself with their prayer? Perhaps their spoken words trembled the water, resonating with all the other pilgrims' prayers, and joining the soft echo of the ancient rock walls. Perhaps what I felt was the sublime power of concentrated belief.

Power in Place

There are places and objects that feel powerful because I am told they are powerful; that are imbued with belief, tradition, and history. In these places, my body responds appropriately. It’s a reflexive respect that brings my voice to a whisper in a church, compels me to take my shoes off at the entrance of a temple, or finds me searching for symbolic foreshadowing in the childhood home of an artistic hero.

Then there are the places and things that hold power for a small, mysterious reason. The childhood toy I can’t get rid of because it would insult the toy. The impulse when moving to a new home — no matter how bare and clean it may be — to sweep the whole place before moving my own things in. Or how, when thrift shopping, there are items that seem to “call” to me, and I say “I think this wants to come home with me” in a tone somewhere between a light joke and simple observation.

If I were to try to explain it directly, I would say “these places and things have feelings too” — a reason that felt obvious as a child, but now sounds foolish. Instead, I might try to say that in this toy, home, and op-shop treasure, there seems to be an energy left by the people who came before; a loop of time lingering in the space.

Time Online

These days, I don’t travel much to sacred wells in distant places. Instead, I spend a lot of time online. Too much time. It’s a place profoundly unquiet, a pummeling noise and a rush of information that leaves me feeling both hyped up and melancholy. I don’t enjoy it as much as I used to, but it’s a place that is hard to stop visiting.

It’s a bit corny, at this point, to refer to Twitter as the ‘hell site’; not because it isn’t true, but because the term is played out. Its hellishness is self-evident, so people stopped bringing it up years ago.

Yet, whenever I’m in a conversation about social media, it always seems to take the same arc: we agree it’s terrible, detail all the ways its ruining things we love, then explain why we still need to use it to stay connected to family, friends, or world events. The conversation will shift to the parts of the site we love, before we are talking about some hilarious post we saw, then forget our plan to quit all over again.

We know it’s bad, and yet still something holds us. Something beyond its addictive design — a personal attachment we’re hesitant to let go of. What is it that attaches us?

Growing Online

At one point, I considered the internet separate from the world; an imaginary boundless place. As a kid, my house had dial-up internet, and to connect to it required a short ritual with arcane sounds. We also had one phone line, so the internet could not be in the house continually. It was a mysterious world encountered late at night, like catching a distant AM station bouncing off the sky.

The web today no longer feels imaginary, as much as we keep up the refrain that “this is not real life”. Online events have direct, tangible effects on our lives. We see traditional media become odd echos of the online world, newspaper articles detailing the timeline of a supposedly important Twitter thread. Physical buildings are shuttered — from retails stores to community spaces — as the side-effects of an abstract algorithm. The web is intangible, but our bodies feel the full, physical weight of it: tired eyes, slumped shoulders, a racing heartbeat, and a dopamine rush from a buzz on our thigh.

I have a new ritual for being online, a timer I set whenever I sit down at the computer. Every 25 minutes it goes off, reminding me to stand up, stretch my body, and let my eyes focus on some soft, unlit thing. I do this to help slow this intangible world’s lasting effects on me.

We know the web has left a mark on us. What isn’t discussed as much is how much we’ve given back to it, all the remnants of us we’ve left within it.

A Few Sites of Endless Feeling

We’ve lived with the World Wide Web for over three decades. With each year, the amount of places we visit online diminishes but the breadth of activity we do in these spaces grows. Today it feels like there are only a handful of websites, and to these websites we’ve given the full spectrum of our emotion.

To Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, we post all our dumb jokes, sincere fears, daily minutae, and monumental events. We give our theories on the world and all that lies beyond it, plus the occasional restaurant review.

We share art: our own art, the art of our friends, the art that means everything to us and we don’t want the world to forget. We give warnings about art that’s too hateful to share, for it is dangerous and grows more powerful with each reposting.

(We share our art and our vulnerability, an unspoken hope that this piece, this phrase, this post will be the one seen by the right people to bring our deliverance.)

We network, we argue, we interview, we connect. We share carefully edited opinions knowing new eyes are watching, hoping they are impressed. We gaze and savour the updates of someone incredible we just met. We flirt in private channels, and feel ecstatic when they slip an inside joke into a comment on our public post, a gif that cements that this feeling is mutual and real. We date, we fuck, we say I love you, we cheat, we break up — all in a collage of physical memory and digital media so that, when it’s all over, we quit social media because it reminds us of too much. We block. We return, and we accept their friend request.

(Maybe we find the one, and we twine our paths and posts and soon are sharing apartment photos, wedding invites, and baby photos. We start family group chats.)

We rage, we breakdown, we organize, we plead, we act, we protest, and we scream about injustice into what feels like a void. We call out others' silence, and shamefully sit in our own. We think too intensely about a picture of a burger — it’s situated in our feed between two videos of murder, and worry that to click ‘like’ is to send the message that witnessing the cruelty of the world is less important than our friend’s lunch.

We ask for help, ask it to our friends and to a vast, networked beyond: help with a surgery, a web series, and a place to stay. We share a GoFundMe and hope to be saved from a life-rending tragedy and weep at the full green progress bar of our goal reached, an HTML rendition of an answered prayer.

We grieve, we upload every photo and memory of someone we lost and switch their profile page from ‘active’ to ‘memorial’. We visit the pages of those we admired, but never met. We re-read their eerily mundane final post, think of how the grid of images where they shared all their art in progress has become, so suddenly, their complete, collected work. We pore through the life luckily captured and held still on these pages, and remember, and reverberate, and share.

We post again and again to the same few platforms. The platforms that leave us feeling exhausted and drained. We share everything to them; then take a digital detox to recover from it all.

Tangible and Intangible

There is a presence I feel when holding an old childhood journal, as if the book is heavier with my words. There is a presence I feel when holding a lover’s warmth-scented shirt, some essence of them still clothed in it. There is energy built up in our actions — the crackle you feel walking into a room where people just finished arguing, or the pleasant warmth after a party when everyone is gone, but the buzz of people is still mingling in the air.

I don’t think this is imaginary. I think this energy is real. Yet, even though I share far more online than I ever did in a notebook, I do not feel the same sentimental attachment to my computer or phone. They do not hold my words — they are windows to the places where my words are held. There is a small set of online platforms that hold my memories for me and allow me to visit them.

We place our thoughts into input forms set expectantly at the top of the page like an offering dish. We place them in, feeling the full emotion attached to our words, desires, and memories. Then we press submit and they’re whisked away — through arcane technical processes — only to appear again in a second back on the screen as a new piece of the global feed.

Though these processes are obscure, they’re not secret. We know where our words and images go when shared to Twitter, Google, or Facebook. They go to their servers.

Servers as Possessors

The spectrum of feelings we share to a handful of websites all end up travelling to the same type of place: a privately owned server rack in some distant location.

With these platforms, when you message a friend it does not reach them directly. It is sent as a request to a server beyond either of your control, and this server responds to your request by, hopefully, passing your message along. It will also keep this message stored, for as long as it needs or wants to, in a data center owned by the same handful.

The message is translated to a language unspoken by us, where everything is reduced to 1’s and 0’s, off and on, light and dark. Then it’s translated into energetic charge, recorded into a hard drive’s platter as a sequence of magnetized moments. Tiny, physical, but invisible points hold the requested magnetic charge, this energetic impulse, for as long as needed… for in these charged and uncharged points live your words, ready to be recalled again.

I think there’s a presence held in our words and actions that lingers after the sound and motion has passed. I cannot explain it directly, except to say that we move through the world like a brush stroke, our colour left to blend with all that came before. That as we project our thoughts and feelings out to the world, the world holds and reflects them back, like heat from the night earth after a day of full summer sun.

And I think when we share our feelings with the world digitally, that presence is passed along with them down the wire, left to hover within and around the data center with all the rest of our things.

A Separate Cyberspace

When the web was introduced to the general public, it was treated as distinct from the real world, like we’d discovered a second, imaginary earth. John Perry Barlow published the “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace”, which said as much in the tone of an official decree: “Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, a new home of Mind… You are not welcome among us…you have no sovereignty here… Your legal concepts of property, expression, identity, movement, and context do not apply to us… They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here.”

We came to learn, of course, that this was hooey.

The online world is deeply entangled — inseparable — from our “real” world. The cyber world he describes was, from the start, a government project. The things we say and do online have a profound effect on our physical lives, and the infrastructural needs have a profound effect on the natural world in which cyberspace resides.

Data centers sit heavy in our world. They stretch across hundreds of acres in largely remote areas, places that don’t draw much public attention but are well connected to power and cable lines. The natural splendor of the location is important, mainly because it can be extracted to lower operation costs. They are built in high deserts where the cool, dry air offsets the tremendous heat the servers give off. They sit atop underground reserves of water so they can consume it by the billions of gallons. They are placed near coastlines to draw in the seawater for cheap cooling, or deep within mountains to help protect their property against the world-razing wars their owners invariably expect.

It is a compelling illusion to declare the internet as a world with no matter, but it takes a whole lot of matter to maintain the illusion.

Maybe it was once useful to distinguish places on the internet as separate from our place in the world, in the way that you were allowed to leave “meatspace” to become an entirely different person visiting the alien lands of “cyberspace”. But this distinction makes little sense now, cyberspace is more a nostalgic signifier than useful term, and meatspace is really just for people who like saying “meat” out loud.

There is no separation. We are all in it together, overlaid and coexistent. And, from my view, to declare a space of ideas and the mind to be necessarily separate from the world is to deny the world the aliveness and agency it holds.

Sacred and Profane

I’ll be direct: we have given so much energy and intention to a handful of centralized platforms that it’s become metaphysically dangerous. These tech companies are like bootstrapped archons, drawing power from the passion and humanity we share to their sites, and from the continued illusion that this is how it must be.

It’s not bad that we share what we do, as much as we do. It’s beautifully human. This need to share is something we’ve always had, now transposed to a digital space because humans are good at adaptation.

But it is awful how our experiences are commodified, contorted, cut up, and traded. That we cannot share with one another intentionally, but must make an offer to a company’s algorithm. That this algorithm organizes everything into a feed whose curation and shape is intended to draw out our most intense emotions, with the intention to make us vulnerable and easy to manipulate. It is bad that everything we share is picked up into an ad-driven feedback loop that sells an exaggerated version back to us, so that all that we love gradually becomes an inescapable, cynical cliché.

There’s something simple and pure in all that we give to these sites and the power that this raises. And there’s something simple and vile in the profane ways the platforms desecrate it.

However, this isn’t how it must be. Technology is not inevitable, a straight course of progress we can only observe and withstand. It is our dreams made manifest and we can dream different and better.

We can give as much as we do now, but to networks and servers that are actually ours. We can share our hopes and memories directly to one another with no central force monitoring and feeding off our words. We can acknowledge the inchoate energy we build beneath our fingers, amplify it through our communities and families, and store it in revered spaces that hold our own generational force. We can use technology that is intentionally small, local, and humble to the natural world.

We’ve felt the tremendous weight of power that profane tech companies hold. The power comes from us. Why don’t we take it and distribute it among ourselves?

Dreaming Another Future

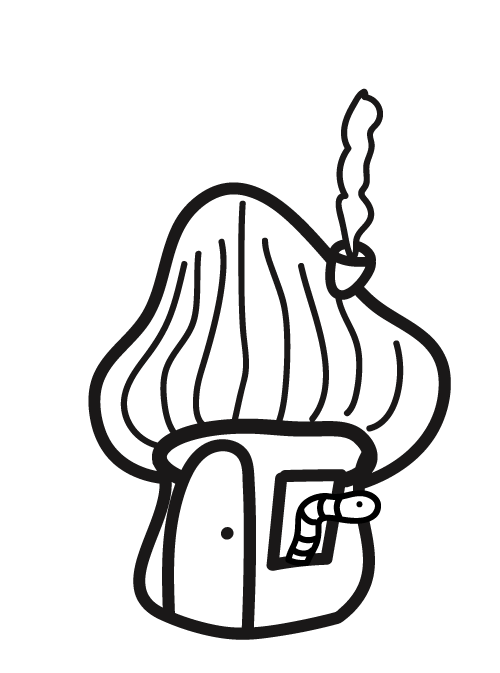

In the spring of a not so distant year, I will return to my hometown to visit the Server Farm. It’s a cheeky title, as the “farm” is just a shed in the center of a garden. In between the rows of community allotments — beans growing up the strings of homemade trellises and tomatoes ripening beneath protective mesh — sits a stark, wooden hut. Its eastern wall displays a calendar against a soft paper-like screen. Its roof is covered in solarpanels reflecting back the sky.

Inside is an eclectic set of computer towers and old laptops. There are bright, plastic bins holding wires and parts, a pegboard of handtools and pamphlets, and a bundle of wires snaking neatly through the machines to a ceiling junction.

This is one of the larger nodes in the town’s network, a condensed form of the town’s cloud. Each node has built up its own personality through the last couple of generations, and this one celebrates the earth and active hands. They’ve set up a tool library in the gathering house next door, and here they host its digital counterpart: a p2p library of downloadable software, schematics, and plans.

Outside is a group of orange-vested children circled around an adult with her hand in the air, holding a spade. It’s the first day of sudo club, a program to keep kids busy during school breaks, where they learn all types of community gardening: from growing a plant from a seedling to installing a mesh repeater on their neighbour’s roofs. It’s a multi-year program of increasing complexity that’s ended up quite popular with the kids. They like the big feast at harvest and leaving funny comments in each others code. It’s rumoured that they’re also using the skills to build their own private network, where they post embarassing memes and talk with fake confidence about drugs.

There’s a café downtown — popular with college freshmen — with homemade lavender shrubs and an ornately decorated Scuttlebutt pub. Here, they can onboard to the town’s social network while they read the “disorientation guide”, with its evocative descriptions of the best local sites, each with its own dumb, regional pun as a web address.

But my favourite node is in the old synagogue by the post office, now the headquarters for our most famous record label. The top floor has the recording studio and a row of flat file cabinets holding every poster of the shows held in town. In the basement is the performance space and server room, a concrete floor with a tower of raspberry pi’s in one corner. This tower, covered in stickers and white-markered tags, holds every album ever made in my town and is the best sync point to the global punk2punk stream: a decentralized, digital, international pop underground.

The label is known for its bravely messy, femme twee sound, but also for creating a tone-based querying language (patched into the punk2punk protocol) that makes it possible to follow a guitarist through the notoriously incestuous band lineups of small-town scenes. Among certain circles, it’s pretty huge.

Each summer, they have a music fest that people come to from all over. On the last night, the label hosts a sleepover in the server room. I will fall asleep beneath the blue glow of our tower, listening to the full sonic history held in its hum. A travelling band plays a droning ambient piece, connecting us to something larger.

Each of these town nodes are small, requiring little more than half a morning’s sun to stay running. They’re more a point of pride than necessity, since the townfolk can connect directly to each other, through personal servers held in all our homes.

In my family’s place, we have a couple servers. One is up by the bay window and hosts a pub, a couple chat servers, and an archive of local comic strips. It connects us to the main town mesh and the greater internet. The other node is at our home’s western wall. It’s on a small altar surrounded by family pictures, placed between a selenite pillar and the St. Christopher’s medal my grandma had clipped to the visor of her car. This server holds the memoir my grandmother wrote, and all the pictures, recipes, sound, and stories we have of her. This node connects to a small, locals-only network, a memorial space created in the air between our houses. I will remember the swell of peace I felt when I uploaded her memoir, knowing it would soon criss-cross over all her favourite places, in the loving mesh that hovers over her old town.

In the not-so-distant future I will have new, inarticulate feelings — moments that feel obvious in the chest, but foolish to say. Like how there’s something in the air here that feels different from anywhere else, a radiance in the radio waves that feels like home.

Image by Angelica Blevins

Zach is a writer, codewitch, and friend. He is the webmaster of coolguy.website and solarpunk.cool and helps run a global solarpunk magic computer club.